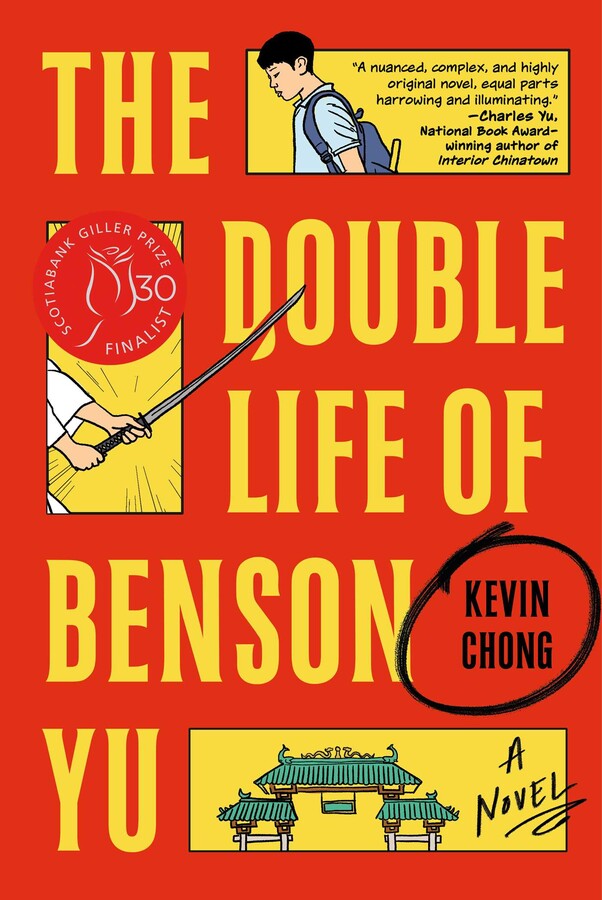

In his latest novel, “The Double Life of Benson Yu,” Vancouver writer, Kevin Chong, uses deeply inventive narrative methods to understand the stories we tell ourselves to process trauma. As a young boy growing up in 1980s Chinatown, Benson finds himself all alone after his grandmother’s sudden death. He is taken in by a neighbour whose intentions are less than ideal. Thirty years later, Benson is a comic book creator struggling with his marriage and alcoholism. What happens when the twelve year-old Benson meets his middle-aged self? Chong shows us how childhood traumas show up in our adult lives, and how memory and perception morph to help us heal, if only in broken ways.

We were lucky to have had Kevin as our creative writing instructor at SFU’s Writers Studio in 2020, the year the pandemic took full control of our lives. Kevin has always been an enthusiastic cheerleader for his students and we couldn’t be more excited for his novel to be on the Giller shortlist. Here are a few questions we put together for Kevin about his new novel and his writing process.

Libby Soper (Instagram: @soper2000):

What provoked you to employ an unusual narrative style in the writing of “The Double Life of Benson Yu”? Did you start out using a more conventional approach and then switch during the writing, or did you always have this approach in mind for the novel?

I stumbled into it. I had planned out the major plot points of the story up till when Benny is sent to his dad, who was meant to be a very bad guy. But I didn’t know how he could be monstrous. And then I came up with my twist. And then I needed to find a thematic justification for it. And then I needed to set it up. The last part, the set-up, was the toughest to figure out.

You have said that the pandemic in part shaped the story you wanted to write, especially in terms of the darkness the story incorporates. Do you think this story would have come out without the onset of the pandemic and the resulting shut-down?

Probably not. When the pandemic happened, I was working on a stage play—a musical comedy, in fact. The staged reading we had planned for it was eventually canceled.

Who was the audience that you had in mind while writing this work?

Diasporic Asians, I think, who I think might get the way Benny is taught to suppress his feelings. I took some pains not to make the location of the Chinatown anywhere specific, although I had Vancouver in my head, and I didn’t want to set the story specifically in Canada either.

Can you talk about your process of editing/revision? Did you write the entire first draft and then edit it, did you edit it after having beta readers go over it, did you edit it as you went?

All of that. I had beta readers but I also had some money from my employer, UBC, to hire freelance editors. There were a lot of revisions and the book made some radical transformation before it came together.

Could anyone else have written this novel? What are your thoughts about authors writing about characters whose backgrounds and identities are not shared by the author?

Probably only I could have written this book. I have thoughts about appropriation and the exploitation of non-dominant voices by folks who have more power. You can write about anyone and anything, but I don’t have to read it or applaud it.

Dora Prieto (Instagram: @primadora_):

Recognizing that you are an experienced novelist, did you feel any moments of breakthrough, or unexpected realizations during this novel that felt significant? For example in terms of craft or process.

Yes, I think it’s taken me a while to find a story that has the narrative urgency this one has.

Visnja Milidragovic (Instagram: @vishmili):

Did you always plan for this to be metafiction? How did the idea emerge?

Nope. I pantsed it. There are elements of metafiction in all of my novels, though this one went way further.

Prachi Kamble (Twitter: @champagneprachi):

In the “Double Life of Benson Yu” you move deftly between time, often, multiple times in the same chapter. Your flashbacks are rich and visceral. The biggest time shift is a thirty-year fast forward that propels us into the second part of the book. How did you manage these shifts and stay organised in your writer mind? Especially since remembering and memory are such important themes in the book, do you think these shifts were a non-negotiable part of the storytelling?

I really struggled getting the right balance of those elements. I had more of it in some places in early drafts, less of it in other places in later drafts.

You write about Vancouver’s Chinatown with a lot of love and care. Even though Benson faces abuse in an apartment in Chinatown, he returns to it [Spoiler Alert] at the end; he is healed by it in a way. Can you tell us what the experience of writing the Chinatown of the 1980s was like? You’ve also written other work set in Chinatown, short fiction and non-fiction. It holds so many stories for you. Can you talk about that?

First off, the book doesn’t specifically take place in Vancouver’s Chinatown, although I had it in mind. I grew up in Ladner and in Marpole, but my grandmother lived in Strathcona and my dad ran a nursing home for Chinese folks there. And I spent long, boring summers there in my grandma’s one-room apartment. So I think the smells of that place and that sense of boredom and loneliness remain vivid for me.

I was fascinated by Benson being launched into the life of his older self as his son, and this being part of his healing. Getting our traumatised child self and our traumatised adult self in the same room would provide for an ideal environment for processing childhood traumas. It is a scenario child abuse survivors often ponder. Can you talk a bit about your decision to have Benson and Yu come face to face? C. himself does not pay for his crimes. What did you envision justice to look like for Benson/Yu?

Yeah, it’s sort of an ideal kind of therapy, isn’t it? But I don’t think Yu is ready for it and so he treats Benny terribly. Justice for Benny/Yu might be to not have their abuser live in their heads.

Your previous work has embodied your love for music and you have written about horse-racing. In this novel you have written about martial arts and comic books. Were you a fan of these topics or did you have to do some research on them? Does it excite you to pick different cultural backdrops like these for your novels? Does new turf like this excite you as a writer?

I know a little about comics but I had to attend some martial arts class and befriend an instructor of a sword-based art called Iaido. I already struggle with having characters who aren’t writers, who don’t share all my biographical markers, that when I can imbue with qualities or experiences that aren’t my own, I don’t mind doing some research.

And yes, I always want to learn something with each new book. That’s why I need more time between books than I’d prefer: I need time to grow and pick up new perspectives.

Were there any novels in particular that you found yourself going back to when writing this book? For style, mechanics of time shift, or structural innovation?

Susan Choi’s Trust Exercise for its metafictional take on abuse. And Charles Yu’s Interior Chinatown for how it turns Orientalism on its head.

You have been writing for many years and you have also been candid about years in which you found it difficult to write. Now that you find yourself on the Giller shortlist what would you tell your young writer self (since we’re already talking about confronting our younger selves!) about writing, perseverance, patience, and maybe even the importance of awards?

My younger self wouldn’t listen to me. He needed to make all the mistakes first. And if he knew that it would take so long, over two decades, to make a national prize list, he’d be depressed. My slightly less old self, like me 10 years ago, would have been very excited, though. He’d just need to sit tight for another decade. Easy.

Buy tickets to see Kevin Chong at the Vancouver Writer’s Festival: Marvelous Meta-Fiction (October 17), Smells Like… 90s Lyrics Night (October 19) and Chinatown: Past and Future (October 21).