Thank god for Shauna Singh Baldwin. She is Canadian. And Indian. And American. This puts her at an extremely unique vantage point from where she can explore matters of multiculturality and global sociology. A Canadian great in her own right, Baldwin has three evocative novels to her name and two collections of short stories. Her work has transformed the canon of modern Canadian literature. She has fleshed the canon out to include voices of Canada’s immigrant populations. I have always loved reading about immigrant experiences so it came as no surprise for me to be drawn to her work. There is nothing more heroic and terrifying than moving to an alien land. Nothing as life changing and nothing that can force you to examine yourself more. Baldwin’s stories address issues of identity, gender and displacement. As a member of the Canadian literary community, she has served on juries for many book awards. I talked to Shauna about her gradual evolution from a MFA student to becoming a respected voice of reason in the literary world.

You have called at least three different countries your home. How did all that displacement affect your personality and your writing?

I think the languages and the colloquialisms of each place influenced me. I still say accha and theek hai from my ten years growing up in India. I still say “eh”. I have a whole lot of things that I pick up in different places. It depends on what I am doing also. I recently translated the “Star Spangled Banner” into Punjabi, so I hope there is a lot of cross-pollination that takes place as a result of moving a lot.

Did moving around a lot make you want to tell stories?

I think you have to assert yourself in every single place. When we lived in India, as Canadians, we had to assert ourselves as Canadian. When we came to Canada, as a second generation coming home, we had to assert ourselves as Indo-Canadian. Then in the US, I had to assert myself as an Indo-American and a Canadian-American. You have to assert yourself everywhere otherwise people do not realise that there are minorities in their midst. The majority always expects the minority to know about them but it doesn’t work both ways.

Is it an advantage to have that outside perspective?

It is a double-edged sword. You don’t see things the way other people see them. The outsider’s perspective is one way of looking at it, misfit is another and cosmopolitan is a third! It depends on how charitable you wish to be at the moment in describing yourself.

You have to be a good communicator if you are on the outside.

You do but everybody is a good communicator. I do not think there are very many people who are strongly on the inside anymore. We are all pretty much outsiders to each other. We have to communicate with each other to make sure we are not outsiders. The tragedy of our existence is that we are all exotic to each other. I don’t think of it as being much more than a microcosm of larger issues. Wherever you go you meet interesting people. It helps to be curious about your environment. If you are not curious then it is no fun!

After completing an MBA you did an MFA. Did the MFA prepare you well for a writing career?

When I did my MFA, I was more interested in learning how to teach than learning how to write. Writing itself teaches you most of what you need to know rather than the MFA. Writing teaches you humility. That is what one needs to learn. It is not a matter of whether your writing is beautiful and wonderful. It is a matter of how well you communicate.

Do you feel more comfortable writing characters of Indian descent?

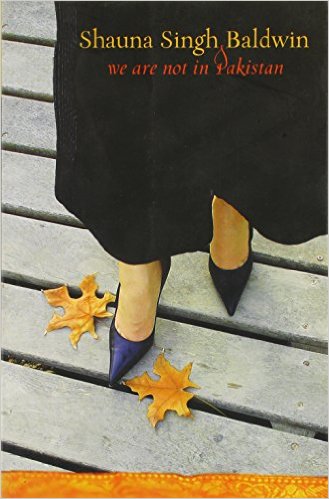

In all of my novels and my short stories, I have always had cross-cultural people rubbing up against each other. I write cross-cultural stories. “What the Body Remembers” is a Partition-based story. There I have both British and Indian characters. In my World War II novel, “The Tiger Claw”, there is a woman of Indian descent who speaks French. She is very French and she operates in a very western environment. I didn’t know anything about World War II history at the time I was writing that novel. I had to learn everything. I thought, “How come I don’t know this stuff?!” I wasn’t taught it because I went to school in India and there it was considered Europe’s war. I also wrote a novella set in Russia. I have written about Pakistani Americans. I write a lot about the Irish in “We Are Not in Pakistan”. It depends on what the story requires and what I am interested in. “English Lessons” was probably the only book where most of the characters are Indian women.

Do you face pressure from publishers, or did you at the beginning of your career, to write “exotic” literature, as it makes you more marketable?

In the early nineties there might have been shock at the idea of writing coming from the Indo-Canadian community. You weren’t expected to do it. I remember the head of a publishing house in India had to be persuaded into publishing “English Lessons” by his own wife because he thought no one would care about Indian women’s stories. The publishing industry in India was very male-dominated at the time. Hopefully it is not so bad now. At that time it was quite a strange thing to be writing about Indian women in India. And it was a strange thing to be writing about Indian women in the USA! There were so many rejections, I can’t tell you. I then started looking at people who were writing similar stories and looked into where they were being published. That is how I found Goose Lane Editions and “English Lessons” became my first breakthrough. It is always a matter of trying to find the right publisher for the right book. Do you find there is pressure?

I feel that readers expect Indian writers to tell Indian stories and they question the authenticity more when they don’t.

Vikram Seth wrote “The Golden Gate” which is set in San Francisco. It doesn’t have any Indian characters, and Salman Rushdie has written stories that are set in Europe and Mexico. I now realise that when I wrote in the voice of a Russian woman, it did not go over so well because people expected Shauna Singh Baldwin to write about Indian people. That is true. But that is their problem not mine, right?

Caucasian writers get questioned less about authenticity. For example there are many Non-Indian writers who tell Indian stories and are rewarded for it.

The question is not about whether you are authorised to do it or not. The main question really is how well did you do it? Did you do it with contempt or did you do it with love? If you did it with love, it shows. It shows in the work. Cathy Ostlere, for example, wrote a beautiful book called “Karma”, which is a novel in poetry. The dialogue there and her understanding of the 1984 Anti-Sikh Pogroms by the state in India are beautiful. Why shouldn’t she write about Indian problems and about Indian characters, as long as she does it with love? I really enjoyed that book. There are writers who write with contempt too. There are Indians writing about Indians with contempt!

You have never been afraid of being political in your work. In “What The Body Remembers” you talk about polygamy and the Partition. In “Selector of Souls” you explore infanticide. Do you ever fear the potential backlash?

Not really because the writing arc is pretty long! At times you feel like you are talking to yourself. And at others you are shocked that somebody has interpreted your work in a completely different way. You just never know what impact your writing will have. You just have to do it. For instance, after years of working on “The Selector of Souls” how could I have known that it would be topical on release? I didn’t know that in December 2012 there would be a gang-rape in India and everybody would go nuts and actually learn the word “misogyny”. What is amazing to me is how novels have been touchstones for people to talk about issues. I love the idea of a novel being a touchstone for disagreement.

Do you think the market has become bigger for female stories? Are people more willing to listen now?

It depends on whom you’re talking to! Female writers are always told that the market is women over 40 who have time on their hands and that men are not reading novels. Well, why aren’t men reading novels? It is not a true statement to say men are not reading novels. But if men are not reading novels and they are reading more non-fiction, they are never getting anybody else’s voice in their head but their own. That is a dangerous thing. If you don’t find somebody else’s voice in your head, and you cannot modulate your thinking to encompass other voices in your head, then you only hear your own voice.

So men tend to lack empathy as a result?

Well fiction of course improves empathy. Not to say that men don’t have empathy to begin with. The question is can we improve empathy by enjoying fiction. And we can! We need to make sure that men are not just channelled into non-fiction. It is not cool for boys to read fiction and that is not good.

You have a unique perspective on race from having lived in different spaces and communities. How do you think race relations have improved in Canada, if at all?

Oh they have definitely improved since I lived there. They have improved in the cities. Let’s put it that way. I really appreciate Quebec and it being a part of Canada. We need to keep Quebec in Canada so that multiculturalism survives. It is because Quebec is in Canada that we have multiculturalism at all and because of Pierre Trudeau, of course. If we lose Quebec Canada will lose all its multiculturalism. I can see from living in the US what that would look like and it isn’t pretty. The US is a monoculture. If you just look at it in terms of sowing seeds in a garden, a monoculture is a very dangerous thing for the land. It is a very dangerous thing for the crops and for the people who eat the crops. A monoculture is a very dangerous milieu. It is an insular form of society. One needs to have diversity.

How do you feel when you go back to India? I guess it is somewhat of a monoculture.

Oh it isn’t (laughs). India is a binomial monoculture. It is becoming a Hindu monoculture.

Do you feel like a fish out of water outside a multicultural environment?

I don’t feel like a fish out of water anywhere. I am in the world and I belong to the world. I have as much right to be here as much as anybody else. But you do have to push a little harder for people to get over their centrism.

Is art a good way to push harder?

Art may be a good way to do that or a futile way. It certainly felt futile after 9/11. I live in Milwaukee. We had a Neo-Nazi come in to our gurudwara in Oak Creek, Wisconsin, and shoot six people. At the support group meetings afterwards, people would say to me, “Oh you’re a writer! You should tell stories about your community!” and I said, “What do you think I have been doing for the last 20 years?” The guy who walked in and shot six people is not reading my novel. He is reading “The Turner Diaries”. So who knows if art does anything? You keep doing it because you have to do something. You can’t do nothing!

How do you feel about the domination of English Literature by older, white, male authors?

In the Canadian academies that has changed quite a bit. I get called to go and speak to classes at different universities, so obviously the canon has been discharged somewhat. Pun intended. Maybe we are progressing in that regard. Growing up I had to read Indian authors on my own. When I first started writing I thought every character had to be blue-eyed and red-haired. I had to overcome that block individually first. I grew up on Nancy Drews and Enid Blytons in India. I had no idea what they were talking about when they talked about ginger beer!

Do you remember how you created a sense of belonging in a genre where no one looked or sounded like you?

Well, I made sure that they looked and sounded like me! I remember reading “Nectar in a Sieve” by Kamala Markandaya and just feeling like things opened up. I was so influenced by Margaret Atwood as a Canadian writer. I read “The Handmaid’s Tale” in the eighties and wondered how she knew so much about how women feel. I then started reading science fiction and could apply it to Indians with no problem. Science fiction is a wonderful way to learn cross-cultural writing because it is so anthropological. You have to learn how to explain a whole new world to people who don’t know anything about it. Science fiction was able to teach me how to write. Ursula K. Le Guin, for example. Oh my gosh. I loved her work. Philip K. Dick, “The War of The Worlds” and H.G. Wells. These are the greats as far as I am concerned, in terms of teaching cross-cultural writing.

I learned a lot about how to process a story from reading Black authors, as well. Toni Morrison, and all the Black writers before me, kept the integrity of their communities and at the same time told stories about understanding the oppressors and forgiving them. You can only forgive if you love your characters. Bell Hooks, for example talks about that.

What is your writing process like? Are you character or plot-driven?

I would say I start with voices and images. I try to figure out where they are. A lot of it arises in antagonism to what came before. You might read something and go, “That’s not the way it is!” and then you say, “Okay, so how would it be if I did it?” That is how “The Tiger Claw” came about. I read so many accounts of Noor Inayat Khan and they were so badly told that I had to do it better. I wanted to regress some of this exoticism that we have had in literature and history. I wanted to fill in the gaps that existed there. You have to look for those gaps.

Why do you love writing? Can you describe how it makes you feel?

I have done it since I was nine years old. I wanted to describe the universe. I was always trying to save the moment. If I was a photographer I would take a picture but a picture doesn’t describe the feeling you have when you are having an experience. I kept a diary when I was very young too. I was writing down descriptions. Now I realise that that was a writer’s notebook. Writing is so emotional when you are actually doing it. Controlling those emotions is so much a part of writing. People ask me, “Do you like writing because it is cathartic?” and I go, “Are you kidding?” It is painful. If it is honest it is painful.

What advice would you give young writers?

I would say that everyone has one novel inside them because everyone has a life. But that is not the issue. You are not a writer if you have just one novel inside you or if you are telling the same story over and over again, which some writers do. The question is whether you move past first world problems like illness and grief to write about moral choices. As soon as you start to write about moral choices then you are in a much more interesting place. You need to get beyond thinly-disguised memoir to actual fiction.

Are you working on anything at the moment?

Many things. I have been working on a book of essays and that is going to be published by the Indo-Canadian Centre next year. That is almost finished. My play “We Are So Different Now” is going to be produced by Savitri Productions in Mississauga in October 2016.

Was it not put on in India as well?

Yes it was. It was “adapted for performance” over there. They changed the title and the story. And they added men because they couldn’t possibly have a play that only had women in it because the sponsors wouldn’t like it you see. So yes it has had its world premiere unfortunately. It even came to New York, off Broadway, and the reviews said “Indian women told to grin and bear it” and I assure you that was not my play. I had a really bad time with that play. I pulled my name off of it. I am hoping Savitri will do justice to it as a feminist play.

How do you refurbish your creativity pool?

You keep reading and you surround yourself with creative people who push and encourage you. You might just be toying with an idea but when someone says, “That might be great!” then you think, okay let me consider this more. That is one of the reasons why I love going to writer’s festivals and listening to writers.

Speaking of the writer’s festival, you are appearing at an event called “Freedom of Expression” at the Vancouver Writer’s Fest. Can you talk a little about it?

It is a very interesting event. Nino Ricci is on the panel. He has been president of PEN Canada. I was on the jury for “The Origin of Species” so I know his work well. Roxane Gay is there. I just finished reading her book, “An Untamed Space”. Oh my god, it was fascinating. Lawrence Hill of course, everyone knows him. He is so sensitive and so topical. I have read “The Book of Negroes” and “Somebody Knows My Name”. These are all very, very important books. One of Hill’s books that I especially loved is a non-fiction book called “Blood”. There he talks about race, gender and genealogy. There are very diverse perspectives on the panel for this event. It is also happening at a significant time when novelists are facing serious backlash over their work. I was in Toronto in May to hear Perumal Murugan talk. He was invited to Toronto and he couldn’t come because of, essentially, an assassination veto on him. He has committed literary suicide because of the brave content of his book. The Indian Taliban has been after him. He has actually withdrawn all of his books for fear that his family might be targeted. This is a terrible situation. I am reading his latest book, “One Part Woman” and it is top notch. Writers are facing terrible problems all over the world. We are very lucky in Canada to have freedom of speech.

We have the freedom to speak or to remain silent. People say to me, “The political novel is too didactic, you know” and “The proper function of a writer is to entertain not to educate”. But your function as a writer is to offend! Your function is not to respect a whole lot. If I were that respectful I wouldn’t write. I am just not a very respectful person! When you say you don’t want political fiction you get navel-gazing fiction and that is no fun.

-Prachi Kamble